Carnot cycle

A Carnot cycle is a certain reversible cycle in the state space of a thermodynamic system. A heat engine that undergoes periodic Carnot cycles is known as a Carnot engine; it converts heat into work. In actual practice, a Carnot engine does not exist, it is an abstract idealization of real engines.

History

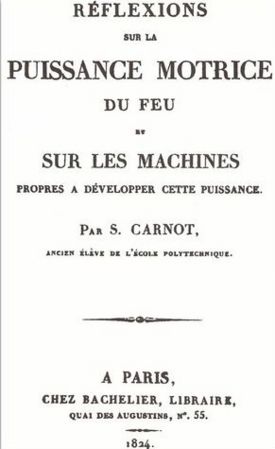

In the early 1820s Sadi Carnot studied the efficiency of steam engines and conceived an abstract, idealized, version of a steam engine as a vehicle for his Gedankenexperimente (thought experiments) in which he mimicked the work of actual engines. In 1824 Carnot published the results of his studies in a booklet (see the adjacent title page).[1] By means of his engine he tried to find answers to questions as: Would it be advantageous to use steam at high pressures, and if so, would there be a limit pressure at which high pressure seizes to be advantageous? How important is the working medium, is steam the best substance, or could air, or any other liquids, perform as well?

Conceptually, a steam engine is very simple; it consists of a piston that cyclically moves in and out a cylinder and is driven by expanding steam. The steam moves from the boiler (hot) to the condenser (cold). Inspired by this construction, Carnot devised an engine that is alternately interacting with a hot and a cold reservoir. When coupled to the hot reservoir, the engine receives heat and performs work on its surroundings—this stage is comparable to the steam engine piston moving out of the cylinder and performing work. When Carnot's engine is coupled to the cold reservoir, it gives off some remaining heat and the surroundings perform work on the engine—this stage is comparable with the piston of a steam engine driven back into the cylinder. While this alternating process is going on, the thermodynamic state of a fixed amount of substance inside the engine changes periodically, that is, the substance goes through thermodynamic cycles. Carnot proved that it is irrelevant for his abstract engine what the actually working substance is, it may be water, an ideal gas, or anything else.

At the time of writing his booklet, Carnot looked upon heat as a conserved fluid, called "caloric", that "falls" from high to low temperature. He thought that his engine converted into work motive power that the caloric received from the hot reservoir; the caloric itself flowed into the cold reservoir. Carnot was inspired by the equivalence of his engine with a water wheel that, in principle, can extract work from the potential energy ("motive power") of water that is initially higher than the water wheel, whereas the water itself is conserved. If "caloric" is simply equated to "heat", Carnot's ideas were contrary to conservation of energy (the first law of thermodynamics) that, however, had not yet been formulated during Carnot's life time.

In the 1850s, R. Clausius and W. Thomson discovered the first law and realized that the Carnot engine converts only part of the heat into work. A sizable amount of remaining heat is given off to the cold reservoir. Although Carnot was not aware of the first law, nevertheless his ideas proved to be very useful to Clausius and Thomson when they formulated the second law of thermodynamics. For this reason it is sometimes stated that the second law was discovered before the first law.

Clausius and Thomson further proved that in the idealized case that the thermodynamic process in the Carnot engine occurs reversibly (which in practice never happens) that it has maximum efficiency, engines based on irreversible cycles or other cycles than the Carnot cycle (the subject of this article), have lesser efficiency (yield less work with the same amount of heat input) than the Carnot cyle.

Technical discussion

Fig. 1. shows of the isotherms 2-3 and 1-4 and the adiabats (isentropes) 1-2 and 3-4.

(To be continued)

- ↑ Reflexions on the Motive Power of Fire, translated and edited by R. Fox, Manchester University Press, (1986) Google books